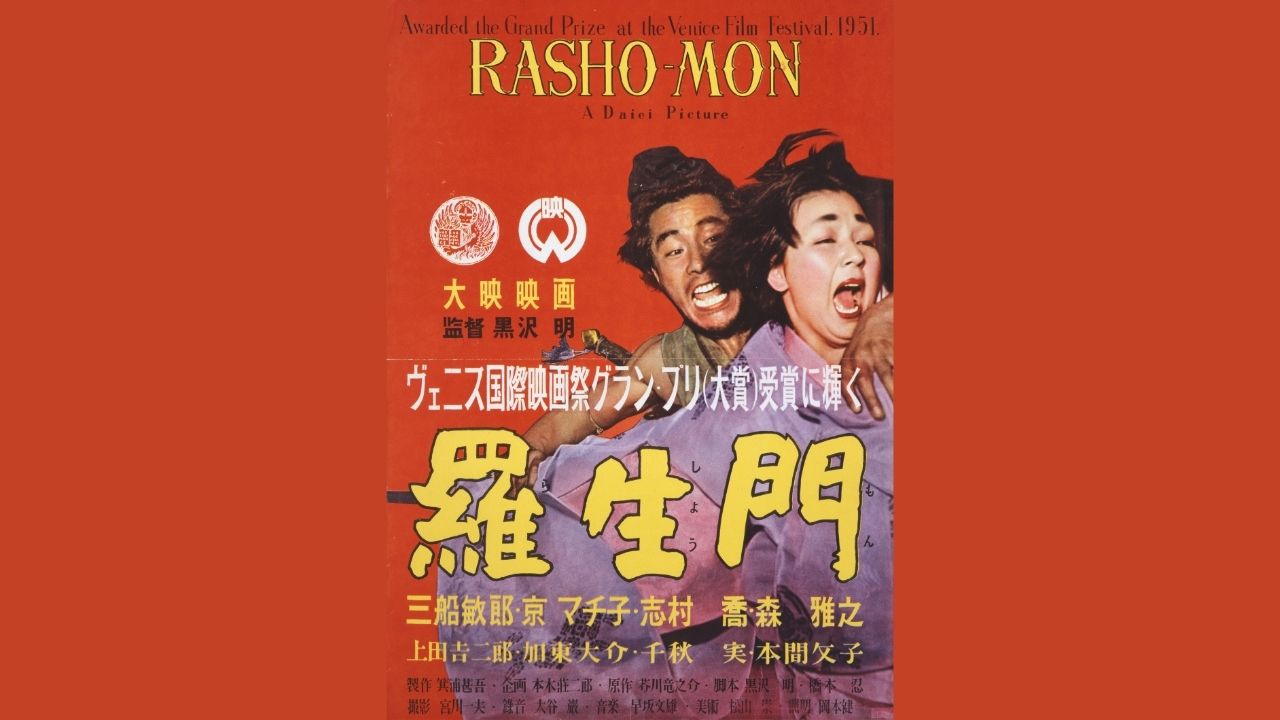

Rashomon took the world by storm. Made during the early years of Akira Kurosawa’s career, long before he was hailed as the greatest of all time, this complex study of the human condition was unlike any movie that any filmmaker had made before. But it was a risk. It didn’t have a concrete ending. His assistant directors didn’t understand it. And the studio head of Daiei Film hated the movie so much that he had his name removed from the credits.

But then Rashomon won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. It was given an honorary Oscar for being the most outstanding foreign language film released in the United States in 1951 (there wasn’t a category for Best Foreign Language Film until 1956). It broke box office records for a subtitled movie. It opened up Japanese cinema to the world. Even the word “Rashomon” has become a part of our cinematic lexicon as there is no other expression in the English language that best describes the narrative style of the movie.

Great movies last. Some of them end up as fascinating relics. Filmic artifacts that give us an insight into our past. Others, like Rashomon, become more and more relevant with each passing year.

Umapagan Ampikaipakan: Watching Rashomon again in 2022 was something of a jarring experience for me. I have seen the movie many times before, but for some reason, this was the first time I realised just how modern it was. Or maybe that’s just reflective of how timeless the message of the movie is.

Bahir Yeusuff: My biggest takeaway from this rewatch is how our experience of Roshomon evolves over time. The thing that I just realised is how Kurosawa has made us a big part of this movie by placing us in the position of judge and jury. We don’t know what is happening. We have to decide which version of the story we believe. Because Kurosawa doesn’t give this movie an ending. Well, he does, but he also doesn’t resolve the case at the centre of this story. Kurosawa tells us the story, shows us the different versions of the case that’s being argued, and lets us decide which one works best.

A lot has been said about Kurosawa’s camera work (he was allegedly the first person to point the camera up at the sun!), his manipulation of background and foreground elements, and his use of movement, but at 40 years old, I finally see Kurosawa’s mastery of narrative.

This movie BEGS you to write a thesis. To discuss and argue it’s plot, and character, and storyline. There is nothing here to hate. Everything is deliberate, and designed, and placed in order to evoke an emotion or a reaction. Rashomon is poetry in motion.

UA: And to do all of that in just 88 minutes too.

BY: Rashomon’s pacing is PERFECT.

UA: There is no filler. Nothing feels repetitive. Every scene, every moment, only serves to add more and more elements to the mystery at the heart of the movie. And yet, it isn’t the mystery that’s important here, but the plight of the people who are caught up in it.

The Usual Suspects

UA: There is only one thing in Rashomon that we know for certain and it is that someone is dead. That is the only objective truth in the movie. Everything else is left to our interpretation. Which sounds like it could be incredibly annoying. But don’t worry. Because this isn’t one of those European arthouse efforts that proclaims nothing is real. This is the opposite.

In Rashomon, everything is real. And not just for the characters in the movie, but also for those of us watching it. Every time I watch the movie, depending on what is going on in my own life, I come away with a slightly different take on what happened in the woods on that day. I believe different accounts. And not knowing for sure has made me want to revisit the movie over and over again.

BY: I’ve always wondered if Kurosawa had a definitive explanation. Did he go into making Rashomon knowing who the murderer was in his version of the story. Was this his Citizen Kane “Rosebud” moment? Is there some little thing he’s left in the movie that is supposed to clue us in on who the actual murderer is? That one thing that will make it so absolutely obvious.

There are so many questions in Rashomon that I want answered. But no answer will ever be enough, because it’ll never be the right one, because it wouldn’t have come from Kurosawa himself. Was the medium real or was it just a scam? Where is the pearl inlay dagger? I feel like if I had the answer to these two questions I could crack this thing wide open.

But I also know that that isn’t the point of Rashomon. The murder feels like just a setting to tell a story about the human condition and how, like the priest, we too are confronted with a sense of absolute despair at humanity. That we too might find a woodcutter who will ultimately restore our faith in mankind.

(I still want to know who killed the samurai though!)

Courage Under Fire

UA: Rashomon is also a movie about how no one person sees another in the same way. Machiko Kyo’s portrayal of the Samurai’s wife is the perfect example of this. Depending on who is telling the story, she is either wholesome and pure, or seductive and sexy, or vicious and treacherous. She could be all of those things or none of them. But Kurosawa uses her character to emphasise the point that we, as human beings, contain multitudes. That we are neither good nor bad. That we are capable of great acts of nobility and cowardice in equal measure. It’s brilliant.

BY: For a movie that is this small – only seven cast members and one horse – Rashomon feels like it has immense scale. Its story of murder, told to the audience from four points of view, can be retold and reinterpreted in ways that tell more about the person watching it than the characters in it. Rashomon is the perfect harsh mirror to each audience member’s humanity. Even after having spent more hours thinking about it than I’d like to admit, I still don’t know who committed the crime. I honestly don’t even have an inkling. The stories are so tightly wound and so well told that there isn’t anything in this 88 minute runtime that would make my guess any more than a guess.

But like the priest, I too am comforted by the fact that the abandoned baby, taken directly into camera, and to us the audience, will have a loving family. Unless the woodcutter was lying about his six children and just wanted the amulet for himself.

UA: The first words spoken by the woodcutter, “I just don’t understand,” should be your guide to watching Rashomon. It’s a call for humility. You don’t have to figure it out. You don’t need to know everything. You just need to approach it with an open heart and an open mind. Which is kinda good advice for living too.

But watching it now, with the baggage and backdrop of the current state of our public discourse, I couldn’t help but feel that Rashomon is the perfect movie for our time. I mean, here you have a story that is told from four different perspectives, all of them both true and false, with absolutely no resolution on what actually happened. Each version is accurate to the person telling the story and yet each version is also fabricated because human beings are unable to talk about themselves without some sort of embellishment.

Every one of them suffers from Main Character Syndrome. They are all the heroes (or villains) of their own story. And they all believe in their own truth and their own experiences. Because to them, it is the only truth that matters.

Now if that doesn’t speak to where we are today as a society, I don’t know what does.

Follow Us