Loosely based on the classic Arabic poem, Layla Majnun tells the story of Layla, an author and academic on a teaching secondment in Azerbaijan, who falls in love with an admirer of her work. The problem, however, is that back in Indonesia, Layla is already arranged to be married to someone else. Heartbreak and unrequited passion ensues.

Umapagan Ampikaipakan: So, I really enjoyed this. I wasn’t sure where they were going to take this classic story, but I was pleasantly surprised by the end product.

Watching this, I kept thinking about every Shakespeare adaptation ever. You can either be faithful to the source material or you can go wild with it and, more often than not, the text is strong enough to handle whatever you throw at it.

Layla Majnun is essentially Romeo and Juliet. We’ve seen this story so many times that it is no longer surprising. (How can it be?) The versions that do stand out, however, boil down to the performances by the leads and whatever cultural nuance is infused into the story. I felt this version stands out for exactly those reasons.

Bahir Yeusuff: I agree completely. And this from someone who automatically avoids a lot of the Nusantara films because I find them dull, or melodramatic. I also don’t enjoy horror movies. It’s a failing of mine that I prejudge a lot of the movies from the region. That said, I am almost always surprised when I do watch an Indonesian movie because the quality is almost always far superior to what our filmmakers end up making.

Now with Layla Majnun, however, there is a historic element that truly piqued my interest. When you told me that Layla Majnun was the first cinema release in Malaysia, in 1934, I was understandably curious.

This version of the movie really subverted my (prejudged) expectations. Overall, I quite enjoyed it for what it was, a love story about two people from different cultures and backgrounds. Also it kind of made me want to visit Azerbaijan.

UA: It definitely made me want to visit Azerbaijan. Making this movie was money well spent by their tourism ministry.

BY: BUT it was never obvious. Or too much. Or hit-you-over-the-head with tourism things. It didn’t feel forced.

UA: Unlike… say… Falling Inn Love?

BY: You shut your mouth.

UA: But you are right about his movie and its history. Besides the cultural cachet of the poem, being the first ever Malay movie means that the story is quite special to us. Cinematically speaking. That version back in 1934 was directed by B.S. Rajhans, who also directed P. Ramlee in his first movie, Chinta. I’ve not been able to track down that first Laila Majnun. I think it’s something that’s been lost to time.

As for this version, the director Monty Tiwa has done just enough to make it stand on its own. He uses the original poem as a point of reference to tell what has become a universally accepted – and relatable – story of forbidden love. This movie takes place in a modern setting, but there is something refreshingly old fashioned about their courting. There was an awkward tension between the two leads that really worked. And given the Islamic undertones, the way their romance blossomed made complete sense.

BY: I’m having a hard time talking about this film mostly because the story (for the most part) moves along quite predictably. But don’t read that as a criticism. I thought the movie was executed very well. From the narrative, to the directing, to the leads, Layla Majnun is a very competently made film. Again, “competent” may sound like a negative comment, but it’s at a level that Pasal Kau never even bothered to try and reach.

In a lot of ways Layla Majnun hits all of its beats very well. Girl from the small kampung dreams of traveling to Azerbaijan to teach with her elder brother. She gets there and everything is as she dreamed. A student falls in love with her. She, I think it’s safe to say, reluctantly starts to feel the same. But she has been promised to someone back home (kind of against her wishes but you know what it’s like, that’s just how it goes), and the story carries on from there. And you’re right, the tension between the leads was an excellent way to develop that blossoming romance. I think there were some awkward story moments – like that Say Anything sequence – that felt a little flat for me, but overall it worked.

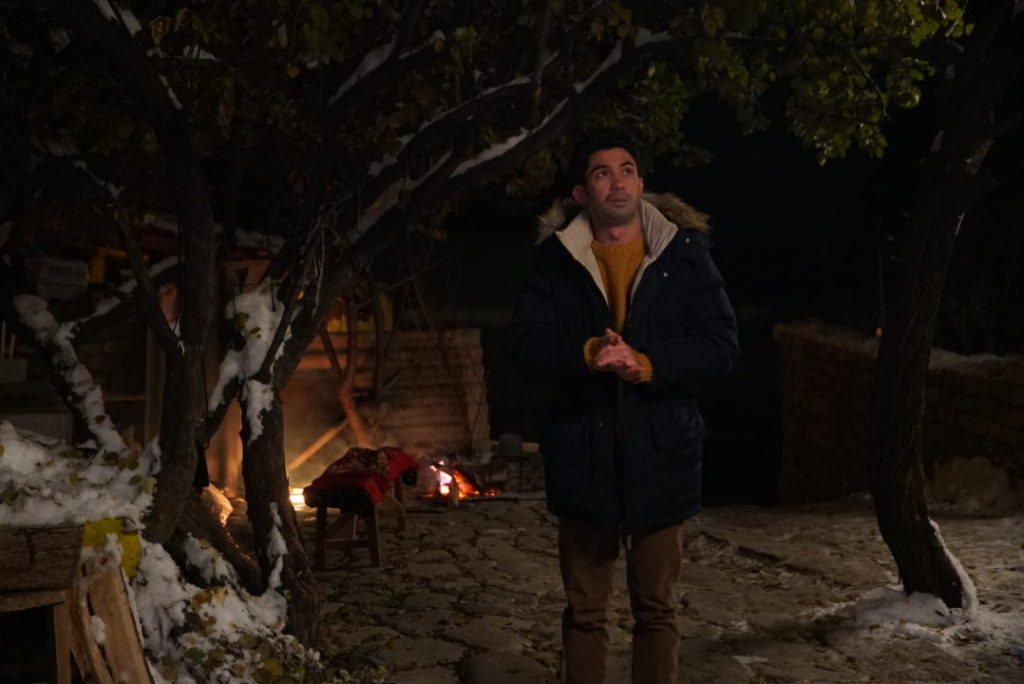

Later in the movie, as Laila leaves Azerbaijan to go back to Indonesia, the heartbroken Samir reacts in a way that, in lesser hands, could be overly melodramatic. Layla Majnun, however, treats it with the respect and care that it deserves. This isn’t a teenager pining for a love lost, this is a man facing true heartbreak. And much like the original 7th century Arabic poem, he goes crazy (Majnūn (مجنون “crazy”, lit. “possessed by Jinn“) at the thought of it. As that sequence was developing, I was preparing my eyes for all the rolling it would do, but it never came. That moment of Samir being a broken man, suffering from a broken heart, was treated well and never milked for the camera.

UA: Did you feel that they had to simplify the dialogue because they wanted to create the illusion of a communication gap between Layla and Samir?

BY: For me that was the only thing that kept kicking me out of the movie. Is there a regular student exchange program between Indonesia and Azerbaijan? I was a little taken aback at the Azerbaijany students speaking Bahasa Indonesia, but I just let it wash over me after a while.

The dialogue wasn’t that simplified I didn’t think. I thought Samir being able to speak Bahasa Indonesia was kind of explained, but I didn’t find it too stilted. If anything, I thought the dialogue was too easy between the two leads. But it didn’t bother me much. Did you find it a problem?

UA: I didn’t find it a problem. But I did find it a little jarring when their conversations would suddenly shift into the poetic. Then again, this is just me nitpicking. I found myself caught up in their romance. I found Acha Septriasa to be incredibly watchable. I believed in her conflict. When Samir asks if he could confess a truth, and Layla replies by saying that if it’s something that would get in the way of their friendship then she’d rather he didn’t. God, I felt that right in the feels.

The only thing I didn’t quite understand was how she was so good at kung-fu. I mean, there are two fight scenes and she’s boss in both of them.

BY: I mean, things can get dicey in the kampung. A girl’s gotta be able to hold her own.

There is one thing that I thought was quite interesting and quite telling of Indonesia’s cultural maturity though. There were a few scenes where Layla is without her tudung…

UA: … and they are scenes that make complete sense, given that she’s alone at home and wouldn’t actually be wearing her tudung.

BY: Oh absolutely. By all accounts, this is a small matter. Acha Septriasa doesn’t wear a tudung in real life. And, as you mentioned, her taking it off in private moments, is completely logical and makes sense. In fact, in Samir’s dream sequence, when Layla is dressed in traditional Azerbaijan garb, she, again, isn’t wearing a tudung. Now story wise, it all makes sense. But…

UA: I knew there was a big hairy but coming…

BY: … if this was a local film, I don’t know how well the Malaysian public would take to that. Or at least the producers of the film would have her wearing the tudung the entire time. I bring it up purely as a comment on expectations and perceptions there. I just found it refreshing that these things are not politicised or overdrawn on religious grounds.

BY: I had finished the movie before you did and I had mentioned that I felt the director had chickened out of a more dramatic ending. Without spoiling it, what did you think? There were quite a few spots where I thought the movie would end, and give it a very Romeo and Juliet style conclusion. What did you think of the ending that we did get?

UA: Wait up. Are we really talking about potentially spoiling a story that’s based on the life of a 7th century Bedouin poet? I mean, surely the statute of limitations on that has long expired?

BY: Fair point. So let’s just give people a spoiler warning here then. (Mild?) spoilers ahead. Maybe stick a photo or an ad here so people don’t accidentally read something they don’t want to.

UA: You know what? I’ll do both.

UA: I won’t lie. A part of me was glad that the both of them got their happy ending. They were such likeable characters that I didn’t think they deserved a tragic end. That said, I think there were enough fake outs that I wasn’t sure how it was actually going to end. Was this the only way for the director to change things up? Would it have been too predictable to have them just die together?

That said, I didn’t think they needed to make Ibnu go all screamy-screamy mustache-twirling evil.

BY: That caught me off guard. He was such a nice guy early on in the film. For him to go from that, to jealous fiancé, to head of a (small) gang, was quite the evolution. I guess you could say that after he had stumbled on the teary conversation between Layla and Samir at the Indonesian Ambassador’s home in Azerbaijan, he decided to butch up. You could also say that he was already showing some of his controlling tendencies during their infrequent phone calls. But yeah, that shift was still a little dramatic.

I appreciated the happy ending. But even that felt a little abrupt don’t you think? There were so many false landings that when the movie actually ended, I felt that the story just stopped in its tracks.

UA: That’s why they had that mid-credits epilogue. “Look everyone, they lived happily ever after!”

I also think they had said everything they wanted to say by that point. I don’t think there was any place left to go. Maybe a special forces raid on Ibnu’s mansion? Then again, maybe they’re saving that for the sequel.

BY: Or maybe Ibnu doesn’t get his comeuppance and that’s why Samir and Layla had to leave the country.

I’m just saying that the ending of the original story would have been a much more emotional ending.

I mean come on! That’s a great ending.

UA: This is also the reason you loved Malcolm & Marie. Why can’t you just let people be happy man?

BY: I don’t see the connection.

UA: You enjoy the tragedy of love. In all its forms.

BY: I’m just saying it’s a stronger ending. I mean, the happily ever after in Azerbaijan thing is great and all but her dying from a broken heart (which is a medical condition by the way), and him roaming the wilderness until he stumbles onto her grave. And in his final moments, carves three final verses in a stone nearby. Camera pans up to the setting sun.

Fade to black.

End.

Follow Us