As we eagerly await Denis Villeneuve’s take on Frank Herbert’s Dune, we’ve put together a series of articles on how the franchise has been adapted, depicted, and received in the 55 years since it was first published.

In this instalment, Umapagan Ampikaipakan looks back at his first encounter with the novel and posits a theory as to why Dune isn’t quite as popular as Star Wars.

The first novel I ever stole was Frank Herbert’s Dune. Which isn’t to say I’ve stolen others. Sure, I’ve borrowed books from friends and “forgotten” to return them (haven’t we all?), but it was never premeditated. Not like it was with Dune.

Let me try that again. The only novel I’ve ever stolen was Frank Herbert’s Dune. I was 14-years-old. And it was from my school library.

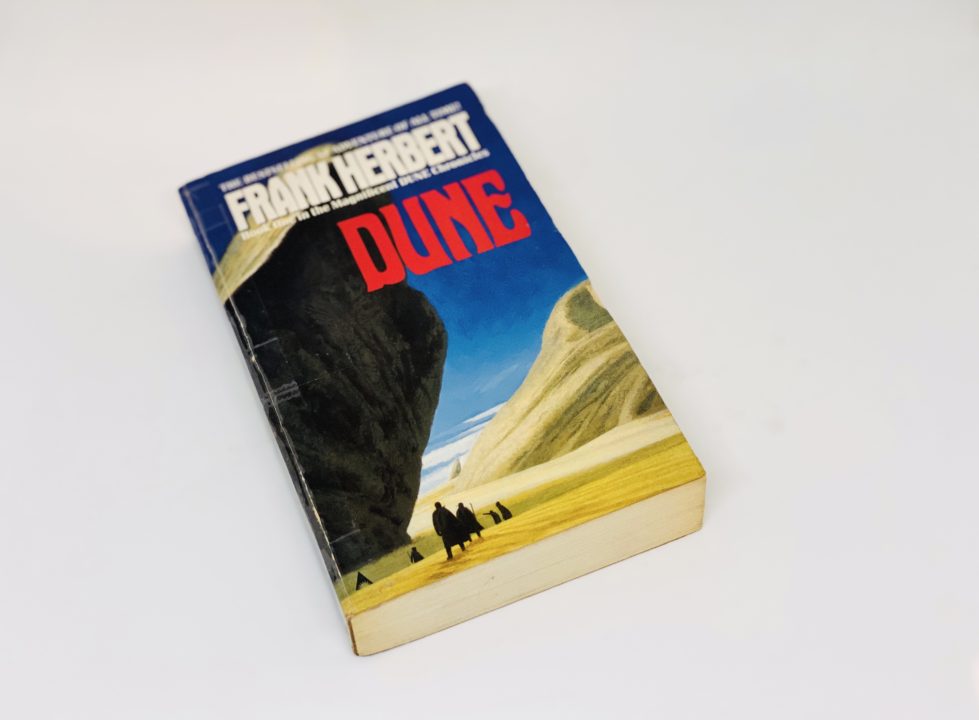

Now, the library in question had a very limited science fiction selection. There were a couple of Asimovs, Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, a tattered copy of Erich Von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods, and this one seemingly untouched copy of Dune. It looked like a recent acquisition. All of the the usual vestments that came with being a library book looked new. The label on its spine, fresh. The brown paper pocket on the inside. crisp. The plastic it was wrapped in perfectly translucent.

I’m not sure why I picked it up. The cover was somewhat nondescript. There were no spaceships or robots. There were just a few, small, featureless silhouettes set against a vast desert. It did, however, boast about being “the bestselling SF adventure of all time!” (Exclamation and everything.)

I’m not sure why I picked it up, but God knows I was hooked from the very first page – utterly spellbound by the bizarre vocabulary that lay before me. Muad’Dib. Bene Gesserit. Kwisatz Haderach. Gom Jabbar, I felt like the young Paul Atreides, mouthing out those strange words, eager to find out what they all meant.

The story of Dune takes place more that twenty thousand years in the future. Set in a feudal society where noble families rule planets in an imperium that’s presided over by a Byzantine emperor, the book begins when Duke Leto Atreides is forced to move his family from their home on the idyllic planet of Caladan to the desert planet Arrakis. The titular Dune.

The Duke is the new ruler of Arrakis. Installed by imperial decree, he is taking over from the evil Harkonnens who ruled despotically over the planet for eight long decades. Soon after Atreides’ arrive on Arrakis, however, treachery and tragedy ensue, leaving Leto dead, and his wife, Jessica, and son, Paul, on the run.

What follows is nothing short of epic. Action and adventure. Conspiracy and murder. All of which drive a story about religious fanaticism, environmental brinkmanship, and messianic salvation. And while Dune reads differently for every generation, it is a novel that has always been relevant. Imagine that it’s 2003 and you’re reading about a white prophet leading a horde of brown revolutionaries against a despot called Shaddam. Or it’s the height of the environmental movement and you’re reading Leit-Kynes’ final thoughts about how “the highest function of ecology is understanding consequences.”

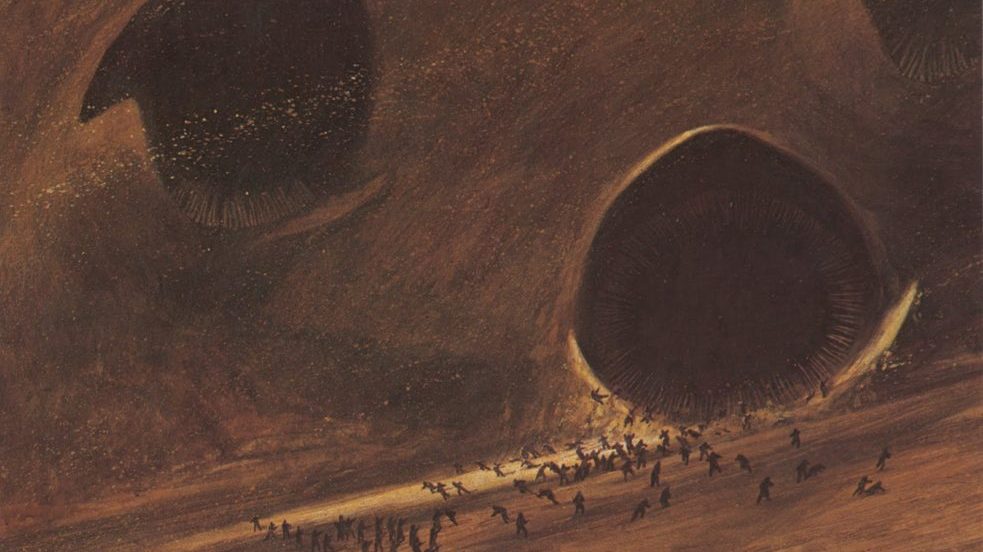

There are mind altering substances. There is Machiavellian manoeuvring. There are political betrayals. There are giant, majestic, monstrous sandworms. There truly is something here for everyone, across every age.

Why then hasn’t Dune experienced the same sort of cultural virality as say Star Wars, or The Lord of the Rings, or Game of Thrones? Why hasn’t this classic of science fiction, which has had such a significant influence on literature, on cinema, on geopolitics, entered the mainstream consciousness the same way as all of the things it eventually inspired?

Part of it has to do with Dune being almost 500 pages. Part of it has to do with the fact that Dune doesn’t contain the usual elements of science fiction. Herbert set the story in a period which de-emphasized technology and threw the focus back on humanity. Which meant no robots, computers, or A.I. And no “pew pew pew.” (There is a key moment in the history of the series, “The Butlerian Jihad”, in which “the god of machine-logic was overthrown,” and the idea that “man may not be replaced” leads to a spiritual reawakening.)

Part of it has to do with there never being a film or television adaptation of Dune that’s captured the imagination of the masses.

At first there was Jodorowsky’s Dune. Or not. The Chilean director’s famously unmade epic remains the one of the greatest “what if” stories in the history of cinema (right alongside Terry Gilliam’s first attempt at The Man Who Killed Don Quixote). It’s legend so large, that there was no way David Lynch’s 1984 effort could ever live up to it; even if Universal hadn’t taken it away from him and stripped it bare.

The Sci-Fi Channel’s turn of the century adaptations of both Dune and it’s sequel, Children of Dune, were mostly okay. And despite being the best possible versions you could see on screen, they still lacked that ineffable quality of a timeless classic.

But the biggest problem for Dune remains Star Wars. It is arguable that George Lucas already made the great Dune movie. A young messiah from a desert planet. An evil emperor. The Bene Gesserit-like Jedi. Moisture farming and sandcrawlers. Lucas took the edge off Herbert’s hard science fiction, threw in robots, space battles, and laser swords, and transformed it into a serialised fantasy.

It is a sad truth that any modern day screen adaptation of the novel will have to contend with how much the source material has already been mined by all those so deeply inspired by it. It is also why a John Carter franchise would have such a hard time getting off the ground. People have seen all of it already. So much so that the original ends up looking like something derivative.

Then again, maybe Dune‘s true impact can’t be found in how prominently it features in the popular consciousness. Maybe Dune‘s greatness lies in its influences. In the refections we see in Star Wars and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. In the sly references made on everything from The Simpsons to Law and Order.

Denis Villeneuve sure has his work cut out for him. Can he pull off a Peter Jackson? It remains to be seen if he can take a property that Hollywood has all but given up on and bestow upon it that greatest of capitalist goals: mass appeal.

Until then, however, there is still, always, Frank Herbert’s Dune. Not his overwrought sequels. Not his son’s travesties. Just the one, original, Dune. That’s the book that taught me about the environment. That taught me to fear false prophets. That’s the book that helped me understand the harsh reality of politics. More than Macbeth. More than Hamlet.

Which is why, everyday after school, I would spend an hour in the library, slowly making my way through the almost 500 pages of that Ace 25th Anniversary Edition of Frank Herbert’s Dune. It took me two whole school weeks of solid reading to finish it. By which point, I had developed something of an attachment to that particular copy.

There are some novels, you see, of which the first copy you read becomes your copy. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. The Hobbit. Little Women. Watchmen. Emma. There are some novels that imprint themselves upon you. That have such a profound impact on your young, impressionable mind, that you feel the need to possess the very same volume that first moved you. I felt that way about Dune.

And so I began planning my heist to liberate that singular copy from those undeserving shelves. My plan was simple. I would wait until closing, feign a scramble, carelessly shoving all the books in front of me into my bag, before rushing out. No one would be the wiser.

And no one ever was.