Most crime serials like CSI and Law and Order are standard, boiler-plate whodunnits where the central narrative driver is discovering the killer’s identity. Rarer still is the howdunnit. Shows like Elsbeth, Poker Face, even going as far back as Columbo, for example, shake up the formula by revealing the killer from the start. The pleasure for the viewer is watching how they get found. Netflix’s new British miniseries Adolescence dispenses with the “who” and the “how” to ask a far more interesting and important question: “why?”

In Adolescence, the Miller family is torn apart when their thirteen-year-old son, Jamie, is arrested for stabbing his classmate Katie to death. While a more conventional series would have focused on the police’s efforts to prove Jamie’s guilt or dwelled on the heartbreak of the victim’s family, Adolescence takes viewers down a different rabbit hole. The series offers an unflinching examination of Jamie and why he became a juvenile murderer.

What makes Adolescence remarkable is that each episode was shot in a single continuous take. The series proves television can be both a visual and an emotional art when form and story unite. The sheer ambition and seamlessly coordinated choreography between the cast and camera crew are miraculous. The continuous take here isn’t just a gimmick; it creates hyperrealism and dynamism of motion for the story. It also induces claustrophobia. Viewers psychologically cannot break away, not even for a second. Like Jamie’s family, we are swept along by the flow of events.

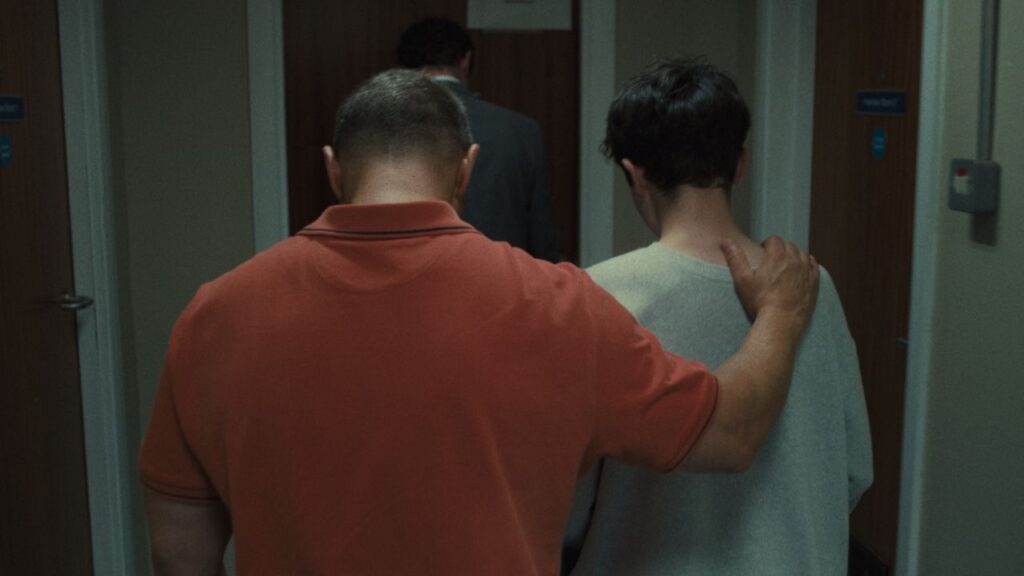

Watching Adolescence felt like experiencing live theatre with a phenomenal cast. Veteran actor Stephen Graham gives a beautifully juxtaposed masculine toughness with tender vulnerability as Eddie, Jamie’s working-class father. Eddie’s struggles to reconcile his son as the boy he raised and loved with the child-killer Jamie becomes is the heart of the series. Watching the physically imposing man break down after tucking in and apologizing to his child’s teddy bear was heartbreaking.

Meanwhile, acting newcomer Owen Cooper, who plays Jamie, is spellbinding. He and Erin Doherty almost single-handedly carry Episode 3 in a profoundly intimate dive into Jamie’s psyche and understanding of manhood. Cooper is a masterful performer, one moment playfully smooth-talking Doherty’s child psychiatrist character, the next flipping into explosive rages as an intentional intimidation tactic against a grown woman. The verbal fencing between them and the gender-based violence of Jamie’s physicality was both thrilling and terrifying to watch.

In just four episodes, Adolescence offers a raw, unflinching exploration of what masculinity means today. The series confronts the influences that shape young males, from online bullying, to parent-child relationships (particularly between dads and sons). The manosphere is also exposed, including the toxic stew of ideas like incels, the 80-20 rule, and the Red Pill. Spouted by influencers like Andrew Tate, these ideologies prove irresistibly attractive to disaffected boys like Jamie seeking someone to blame.

The series reminded me of the infamous Thompson and Venables murder case in the UK in 1993. Both 10 at the time, Thompson and Venables kidnapped and slaughtered two-year-old James Bulger just for fun. Murders involving child victims understandably always prompt enormous public grief for the loss of an innocent life. Yet murders involving child perpetrators are much more complex, confronting society with the uncomfortable spectre of violence, guilt, and corruption from those who should be most innocent.

Scholars who study youths have noted a worrying trend. In the UK, and in much of the “democratic” West, there has been a marked hardening against child offenders. Law enforcement and public attitudes have embraced more hard-lined punitivism for juvenile criminals and kids in general. Often, youths are seen not just as in trouble but as troubled, and just plain trouble. Episode 2 of Adolescence shows even schools have absorbed this at-siege mentality. When the police visit Jamie’s school, all the adults there behave like they’re under assault by angry delinquents.

Adolescence shows that child-killers can spring from even the most stable families. The Millers did everything right but couldn’t stop Jamie from being poisoned by the manosphere. The series opens critical discussions that must be had, especially with young people, and especially because they are having these conversations already, whether or not adults know it. Admittedly, I only found out about Andrew Tate recently when listening to a discussion among my Film Studies undergraduates. That was a real education about a world unknown to me. Fortunately, my students, both male and female, critically reject Tate’s misogynism, proving that such noxious ideologies do not find purchase among all youths.

Follow Us